The high costs of “free” Services

I have written recently about my increasing concerns about the practices of the internet monopolies – Google (including its YouTube service) and Facebook especially – as I have done more reading of works by prominent critics such as Roger McNamee and Tristan Harris, and seen the real-world effects of these platforms, which are terrifying across so many dimensions.

Reading the fine print

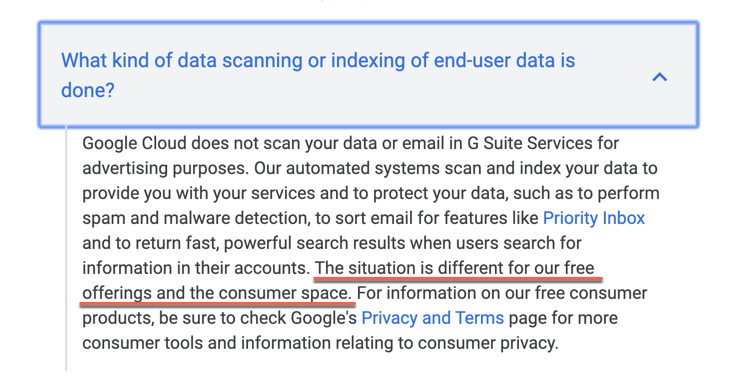

Because goodcounsel uses Google’s G Suite for email and other apps (for now), I have had to review their terms to ensure that client data is properly protected. (It is.) In the course of doing this review, I was struck by a key difference between the online term for G Suite, which is a fee-based service, and those applicable to the personal gmail service, which does not require payment. If you want a simple illustration of the notion that “privacy comes at a price” in our current era of internet monopolies, read the below:

Paying with your privacy

As this FAQ on the Google website makes explicit, my data is being used for advertising and other purposes in Gmail in a way that it is not in G Suite. In other words, Gmail is not “free.” I am paying with the privacy (or lack thereof) of my data and by letting Google exploit my data in various ways.

Some argue that trading one’s data and privacy for a package of services that is provided payment-free is a rational one. I do not accept this. First of all, the ways in which Google and other internet giants use our data is opaque and ever-changing. Most of us don’t – and don’t have the time to – truly understand what we are giving up for our “free” email and other tools. (Though Google seems to be trying to write its policies in clearer language and now employs videos to explain them, it’s still a daunting, time-intensive task to figure out what they are up to.)

Moreover, the premise of this argument is that the price we pay is fair – which in a capitalist system, means determined by a competitive market. But given the monopoly power that Google wields, we certainly cannot say that. If Google was broken up and/or better regulated then, as Roger McNamee persuasively argues in Zucked: Waking Up To The Facebook Catastrophe, they and others would still provide the same services and still make plenty of money doing so – just not the kind of money that a monopolist makes. If you doubt it, as McNamee suggests, just check out Google’s high operating margins, which suggest an uncompetitive market.

Monopoly games

I would also observe, also, that Google is taking a page from Microsoft’s old monopolist playbook, incorporating features into its product offering that were developed by others , thus squashing competition and stifling innovation in the process. Just as Microsoft built Internet Explorer and then bundled it with Windows to take advantage of Windows’ monopoly market share and thus destroy the upstart Netscape, Gmail seems to keep incorporating features from products I have used, such as RightInbox and Boomerang, features like delayed send and email snooze. (A pretty remarkable list of how unoriginal Gmail’s product features are is here.)

A benign platform operator creates an ecosystem for independent developers, who can profit as they innovate and make the platform more useful for users. Parasitic platforms like Google and Facebook enable and encourage independent developers, only to adopt their ideas or otherwise pull the rug out from under them down the road.

Look at the big picture

Before you accept the facile argument, “hey, these products are cheap and useful, why worry?” (which seems to be the current stance of antitrust law), consider the hidden costs (to our individual privacy and our democracy more broadly) and whether we could still enjoy the benefits of free (or inexpensive) tools in a more competitive, non-monopolistic environment. For this to happen, the government is going to have to step in and act.

Categorised as: Internet monopolists, News and Views